By Paul Prettitore

http://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wboper/16120.html

Policy Brief:

The justice sector provides citizen avenues to enforce rights and hold government accountable for delivery of public sector services. Within the formal sector, courts and lawyers are the primary providers of justice services. While access to such services can prove complicated for all citizens, poor persons face additional obstacles in accessing due primarily to the inability to pay associated fees. The inability to access courts and lawyers puts the poor at particular disadvantage in a number of circumstances, for example: resolution of intra-family disputes; complaints involving access to social safety nets; and disputes related to employment abuses. Governments can attempt to fill these gaps by introducing new services, such as legal aid and special funds providing payments for alimony or child support, or making existing services more accessible, for example through tools for citizens to represent themselves in court. When targeted properly to the poor, these initiatives can help ensure they are aware of the rules that affect them, and are able to enforce these rules in an efficient and effective manner – an approach recommended by the World Bank as a means to address poverty.

Understanding the demands and priorities of poor persons is important to effectively target new services and improve existing ones. Yet in the MNA region understanding of demand is considerably lacking, as is data that would help identify priorities. To better understand demand, the Department of Statistics of Jordan and the Justice Center for Legal Aid (JCLA), a Jordanian civil society organization, developed and implemented a survey of 10,000 households focusing on the justice sector – the first of its kind in Jordan.[1] Its primary objective was to identify the most common types of legal disputes and identify the characteristics of the households and individuals involved in the disputes. Questions on use of services focused on those provided by courts and lawyers. The data obtained covers a number of key issues within the justice sector, including: identifying the most common types of legal cases; access to courts and lawyers in terms of costs and awareness of services provided; access to, and familiarity with, legal aid services; and the economic characteristics of families and individuals with legal disputes. Further disaggregation of data based on monthly expenditure levels and the gender of respondents provides valuable information on the types of issues most affecting the poor and women.

Analysis of this data suggests the following findings:

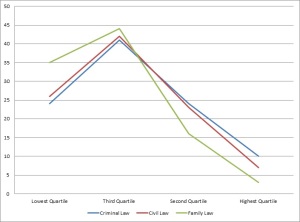

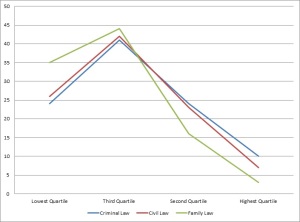

The poor and near-poor have considerable need, relative to wealthier individuals, for court and lawyer services but less access. More than two-thirds (68%) of survey respondents reporting an actionable dispute fall into the two lowest categories of expenditure levels, which roughly correspond with the categories of those in poverty and those just above the poverty. The latter group likely falls below the poverty line for certain periods but overall are not classified as poor, and as such are placed in a situation of not qualifying for legal aid services, which are mostly reserved for the poor, but at the same time are not likely to have the financial resources to pay court and lawyer fees. Only 6% of respondents fall into the highest expenditure category. (Figure 1) The increased reporting of disputes by the poor and near-poor, in comparison to wealthier respondents, was consistent along the three categories of disputes – civil, criminal and family law. This data demonstrates the importance of targeting services to the poor and near-poor, and the need to experiment with service delivery models that take into account high demand and the limited resources of a middle income country. Legal aid services – broadly covering information, counseling and representation by a lawyer – are usually reserved for the poor. Tools allowing individuals to represent themselves in court (pro se representation) can benefit the near-poor as well.

Figure 1 Dispute Frequency (by expenditure level)

Source: Jordan Demand for Legal Aid Services Survey 2012

Poorer persons tend to experience different types of disputes than wealthier ones. Overall, poorer persons form the bulk of respondents affected by family law disputes. This is roughly consistent with global trends, based on provision of legal aid services. Respondents in the lower expenditure categories were much more likely to be involved in personal family law disputes, such as divorce, alimony, child support, inheritance and access to dowries, than richer respondents – around 80% of those in the lower two expenditure categories versus roughly 20% in the higher two expenditure categories. And within the category of family law, poorer respondents were more likely to be involved in alimony and inheritance cases, and richer ones in cases involving separation/divorce and return of dowries. This finding highlights the ineffective targeting of legal aid services in Jordan, which are obligated only in cases involving serious crimes but are generally not available for family law cases, which are handled by religious courts.

Very few Jordanians are aware of the availability of legal aid services, but most would use them if they had the option. Roughly 98% of survey respondents were unaware of existing legal aid services. And ofthe 2% of respondents aware of legal aid, only 17% tried to access it. The primary reasons for not accessing services were lack of knowledge of how to reach service providers (35%), not actually needing services (33%), and complicated procedures for accessing services (27%). On a more positive note, 78% of respondents that sought legal aid services were able to secure them. However, more than 80% of respondents stated they would access courts and lawyers if they received assistance in paying fees.

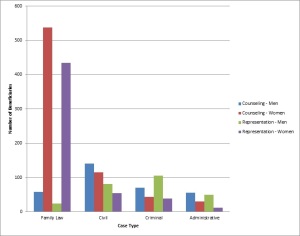

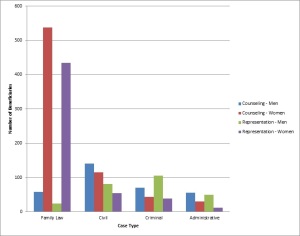

Women and men tend to experience different frequencies and types of disputes. As individuals, men were three times as likely as women (75% for men versus 25% for women) to report having a legal dispute in the last five years. Of the households reporting disputes, 92% were headed by men. This is likely due to a combination of men’s legal and social roles as head-of-household, and women’s low labor force participation (22%) and limited control of economic assets. Women are considerably more likely to report disputes related to family law cases (44% of women versus 11% of men), and less likely to be involved in criminal and civil matters. When poverty is considered as a factor, the gap between men and women related to personal status disputes widens even further. Analysis of the caseload of the Justice Center for Legal Aid, a Jordanian civil society organization and the largest provider of legal aid services in Jordan, demonstrates that poor women were almost ten times as likely to request counseling for family law issues, and eighteen times as likely to qualify for legal representation for such cases based on poverty status. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Case Statistics, Justice Center for Legal Aid (May 2013)

(Source: JCLA Caseload)

Women’s and men’s use of courts and lawyers also varies. Access to financial resources in addressing disputes is more of a constraint for women than for men, and even more so for female-headed households with women and female-headed households more likely to avoid filing claims in court because of lack of financial resources, and to proceed to court without a lawyer because of inability to pay lawyers’ fees. Women are also more likely to avoid going to court because of social norms (26% of female respondents versus 17% of men), and are perhaps more likely to seek assistance from civil society organizations. While there are no formal restrictions on women accessing court services, anecdotal evidence strongly suggests women face societal pressures to avoid pursuing disputes through formal institutions. At the same time, women may also be more dependent on courts, since they are less likely than men to resolve disputes amicably. Given the unique obstacles they face, women are more negatively impacted by the lack of comprehensive legal aid services. Since the survey suggests that awareness of procedures for accessing courts and lawyers varies little between men and women, the key issue is enhancing mechanisms to use that knowledge.

[1] ‘Statistical Survey on the Volume of Demand of Legal Aid Services’, Department of Statistics of the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation and the Justice Center for Legal Aid (2012).